Self-Portraits Show Perception of Illness Remains Despite Cure

If a picture is worth a thousand words, Professor Jitske Tiemensma’s research speaks volumes. The UC Merced health psychologist uses self-portraits to assess how patients feel about their illnesses.

In a study published recently in the European Journal of Endocrinology, Tiemensma found that people with acromegaly, a growth disorder that can lead to gigantism, still perceive themselves to be afflicted even after receiving a clean bill of health from doctors.

“Patients are labeled ‘cured’ by medical doctors, but still feel like a patient with acromegaly,” Tiemensma said. “We think that these drawings have the potential to function as a source of information healthcare providers are less likely to receive otherwise.”

“Patients are labeled ‘cured’ by medical doctors, but still feel like a patient with acromegaly,” Tiemensma said. “We think that these drawings have the potential to function as a source of information healthcare providers are less likely to receive otherwise.”

Acromegaly is a disorder caused by the over-production of growth hormone during adulthood. It can lead to gigantism in children; in middle-aged adults, the results are enlarged bones in the hands, feet and face. It’s also rare — affecting about 60 people per million, according to the U.S. National Endocrine and Metabolic Diseases Information Service.

Treatment can reverse the effects of the disease, but patients usually do not fully return to their prior appearance, Tiemensma said. Patients with active acromegaly report a lower quality of life due to social issues, psychological symptoms and physical complaints.

“What our research shows is that even after treatment and cure, most patients still report a lower quality of life than healthy individuals,” she said.

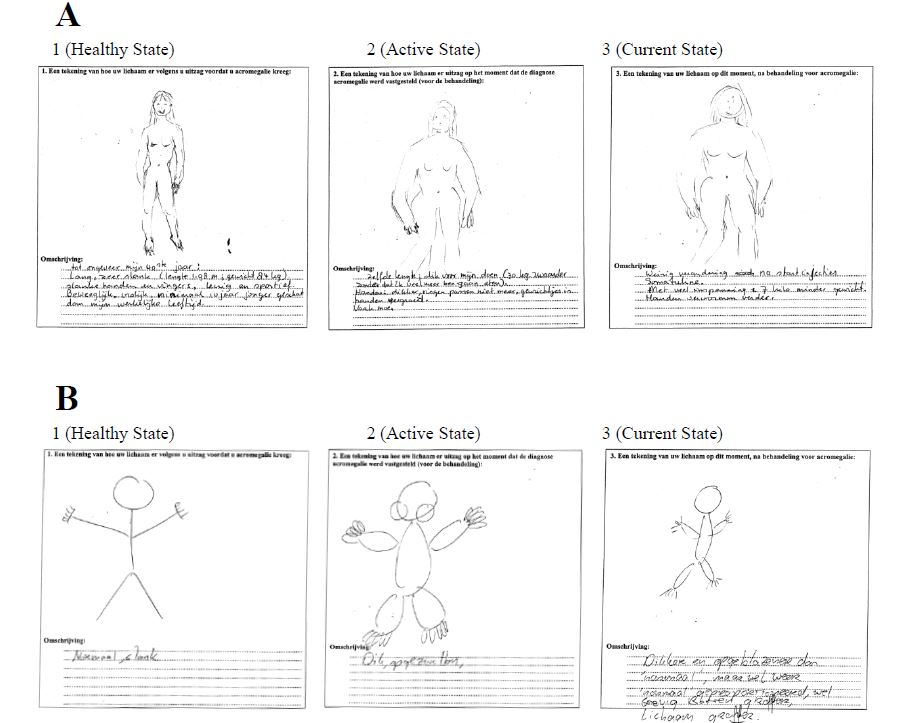

This is shown by a series of drawings the patients are asked to create. The first is a picture of the patient before the disease, the second is when the disease was active, and the third is of the present, after being cured.

The patients’ first drawings showed healthy individuals and reflected no pain, negative emotions or symptoms. However, the head, hands and feet in both the second and third drawings were significantly larger and wider compared to the first, suggesting the patients still perceive themselves as suffering from acromegaly even though doctors consider them successfully treated.

The researchers also found that patients who drew larger drawings of their symptoms had more negative perceptions about their illness and suffered from a lower quality of life.