Researcher’s Work Helps Recognize Aggressive Breast Cancers

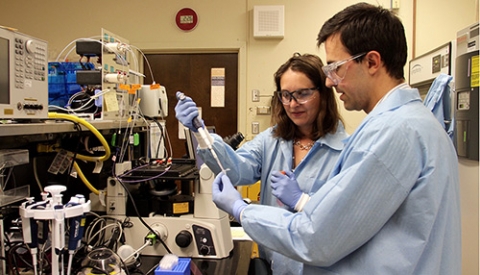

Adjunct Professor Gabriela Loots is studying why certain cancers prefer to metastasize to bone.

To discover the answer, she must mark and trace some of the tiniest particles in the human body. She’s using novel technology developed by a fellow UC Merced professor to do just that.

Loots, who works mainly at Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory, recently earned a three-year, $768,803 grant from the U.S. Department of Defense to continue her work.

“Once these kinds of cancer reach the bone, they form very aggressive tumors,” said Loots, a bone biologist. “We want to know what it is about the interaction between bone and cancer that causes this life-threatening event.”

“Once these kinds of cancer reach the bone, they form very aggressive tumors,” said Loots, a bone biologist. “We want to know what it is about the interaction between bone and cancer that causes this life-threatening event.”

Working with UC Merced graduate students, Loots is trying to identify, characterize and potentially exploit the information packaged in different types of extracellular vesicles to determine if they can distinguish aggressive forms of breast cancer that rapidly spread in the body.

Like all cells in the body, cancer cells package proteins and RNA into vesicles that are sent throughout the body. Normally these packets of molecules and genetic information travel from cell to cell performing essential functions. However, in aggressive cancers, it is hypothesized that those packets can act as scouts to find other organs in the body to expand the cancer's reach beyond the initial site.

Cancer metastasis has long been modeled as a tumor breaking off and landing somewhere new, where it forms a secondary tumor. New studies suggest that cancer-derived vesicles go to new sites first and make them more favorable for tumors to land and grow.

Loots’ team looks for unique information contained in the vesicles that manipulate and prime the environment in the bone, a main site of metastasis for breast cancer. The main cause of death from cancer is metastasis to bone, brain or lungs.

One of the aspects Loots’ team will look at is whether there are differences in the vesicles between metastatic and non-metastatic cancers. Her methods, though, can be applied to any kind of cancer.

Being able to distinguish the contents of the vesicles could lead to further research investigating the prevention of metastasis by either intercepting or stopping the vesicles from being released altogether, or by using their cargo as biomarkers.

But the vesicles are far too small to allow for the measurement of RNA movement with any conventional method. The unique RNA-labeling approach developed by Professor Michael Cleary, allows Loots and her team to mark and observe tiny amounts of RNA associated with cancer.

The technology allows Loots’ team to detect what would otherwise be undetectable.

“We can use this enzyme in any system, and radioactively mark the RNA that is made by cancer only,” Loots said. “Then, using accelerator mass spectrometry, we can look to see if we find the marked RNA in healthy cells of the body, because that kind of spectrometry can quantify picomolar amounts of RNA.”

Loots is trying to recruit more graduate students for the project.

"Everyone has been touched by cancer in one form or another,” Loots said. “If we can prevent it from metastasizing, that would be a huge breakthrough.”